- 590 [ca] Born in Ireland, became a monk on the Scottish island, Iona.

- 635 Consecrated a bishop, sent to Northumbria as a missionary, founded a monastery on Lindisfarne, now called Holy Island

- 651 died in Bambrugh

- August 31 Feast of St. Aidan

With thanks to St. Aidan’s Church, Malibu, CA:

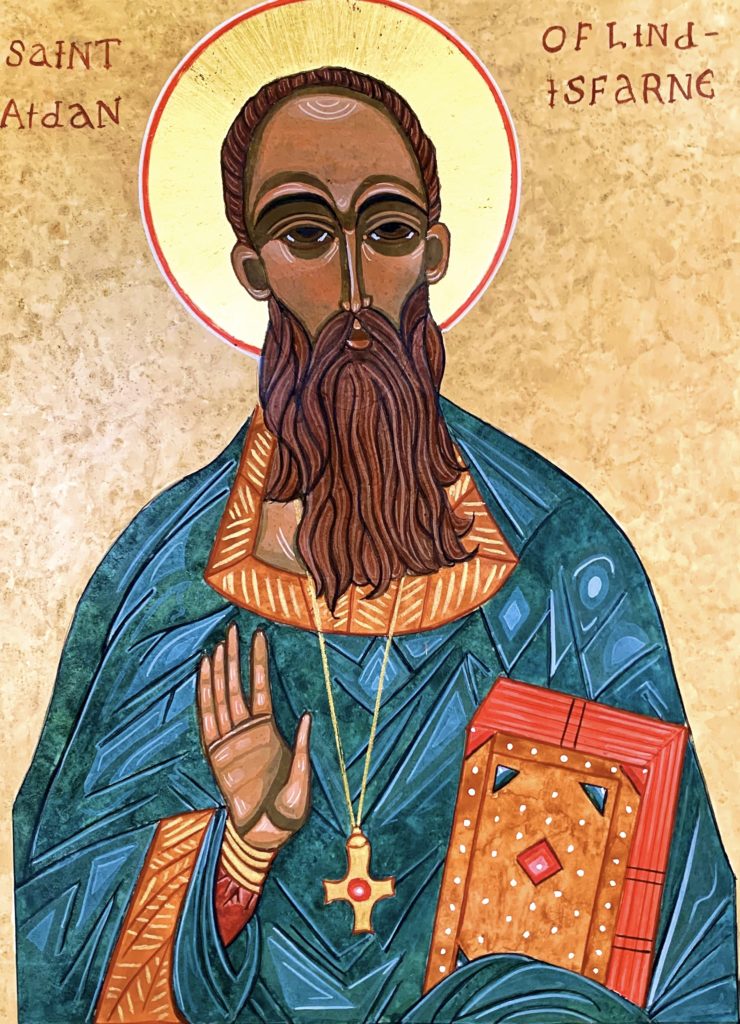

In the seventh century, St. Aidan was the Bishop of Lindisfarne, an island in the North Sea, where he converted the Celts living in England’s far north. Little is known of the saint’s early life, save that he was an Irishman, possibly born in Connacht, and that he was a monk at the monastery on the island of Iona in Scotland.

St. Aidan lived in a time of conflict in the British Isles. There was conflict between Christianity and the pagan religions of the Anglo-Saxons and conflict between the Christianity of the Celts and that of the Romans.

In 633, King Oswald of Northumbria determined to bring Christianity to the pagans of his kingdom. From his fortress of Bamburgh, he sent messages to Iona asking for missionary monks to come and minister to his people.

The first monk sent, Corman, met with little success due to his austere disposition. He returned to the monastery and reported he was unable to achieve anything because the people “were ungovernable and of an obstinate and barbarous temperament.” St. Aidan was at the conference and commented to the failed missionary, “Brother, it seems to me that you were too severe on your ignorant hearers. You should have followed the practice of the Apostles and begun by giving them the milk of simpler teaching, and gradually nourished them with the word of God until they were capable of greater perfection and able to follow the loftier precepts of Christ.” This observation by St. Aidan convinced all in attendance that he was the man to attend to the missionary work in Northumbria.

He arrived in Northumbria around 635 accompanied by twelve other monks and was established as Bishop of the area. King Oswald gave him the island of Lindisfarne (now known as the Holy Island) for his Bishopric. It was eminently suitable for him since the island was cut off from the mainland except twice a day during the periods of low tide, when a land bridge was uncovered. It provided both solitude and a base for missionary work. St. Aidan established an Irish-type monastery of small wooden buildings and circular dwelling huts. There the monks spent time in prayer and studious preparation before venturing out into the community to spread the gospel.

Aidan lived a frugal life and encouraged the laity to fast and study the scriptures. He himself fasted on Wednesdays and Fridays, and seldom ate at the royal table. St. Aidan tirelessly engaged in preaching and pastoral work. He traveled mainly by foot and visited all he came across. As St. Bede tells us, “Whether rich or poor, if unbelievers, to embrace the mystery of the faith, or, if already Christians, he would strengthen them in the faith and stir them up, by words and actions, to alms and good works. He was accustomed not only to teach the people committed to his charge in church, but also feeling for the weakness of a new-born faith, to wander round the provinces, to go into the houses of the faithful, and to sow the seeds of God’s Word in their hearts, according to the capacity of each.” When a feast was set before him he would give the food away to the hungry. The presents he received were given to the poor or used to buy the freedom of slaves, some of whom entered the priesthood.

Aidan had to ensure that his efforts did not die with himself and his Ionian monks. St. Aidan realized from the first the value of education and established a school to train the next generation of Christian leaders for Northumbria. The monastery he founded grew and helped found other monasteries throughout the area. It also became a center of learning and a storehouse of scholarly knowledge.

Aidan and King Oswald worked hand in hand, especially at first, since St. Aidan and his monks could not speak the language of the people. King Oswald translated for them until they became proficient in English. In 642, King Oswald was killed in battle against the pagan King Penda. King Oswin was appointed as Oswald’s successor. He also supported Aidan’s apostolate.

Aidan preached widely throughout Northumbria, traveling on foot, so that he could readily talk to everyone he met. King Oswin presented St. Aidan with a fine horse and trappings so the Bishop would no longer have to walk everywhere. No sooner had St. Aidan left the King’s palace when he came across a poor man asking for alms. The bishop gave the man his new horse and continued on his way. St. Bede has left us the following account: “The King asked the bishop as they were going in to dine, ‘My Lord Bishop, why did you give away the royal horse which was necessary for your own use? Have we not many less valuable horses or other belongings which would have been good enough for beggars, without giving away a horse that I had specifically selected for your personal use?’ The bishop at once answered, ‘What are you saying, Your Majesty? Is this child of a mare more valuable to you than this child of God?’”

After that response, the King humbled himself before his Bishop and said, ‘I will not refer to this matter again, nor will I enquire how much of our bounty you give away to God’s children.” It was later that evening when St Aidan had a premonition of King Oswin’s death saying to his attendant, “I know the king will not live very long; for I have never before seen a humble king. I feel he will soon be taken from us, because this nation is not worthy of such a king.”

It wasn’t long after this incident in 651 when King Oswin was murdered in Gilling, by his cousin. Eleven days afterward, St. Aidan also died after serving 16 years in his episcopate. He had become ill and a tent was constructed for him by the wall of a church. He drew his last breath while leaning against one of the buttresses on the outside of the church. This beam survived unscathed through two subsequent burnings of the church and at the church’s third rebuilding, the beam was brought inside the church and many reported miracles of healing by touching it.

What St. Aidan had achieved may not have been clear to him at death, but subsequent history showed the strong foundations and lasting success of his mission. The missionaries trained in his school went out and worked for the conversion of much of Anglo-Saxon England. Saint Aidan of Lindisfarne is credited with restoring Christianity to Northumbria.

One story has St. Aidan saving the life of a stag by making it invisible to the hunters. Even though this miracle has also been attributed to St. Aidan of Ferns, the stag is one of the heraldic symbols associated with St. Aidan since the stag symbolizes solitude, piety, and prayer. St. Aidan’s crest is a torch, a light shining in the darkness, since ‘Aidan’ is Gaelic for ‘fire.’ We may also see St. Aidan portrayed with a tent reminding us of his death.

St. Aidan’s feast day is on August 31.